Miller Hull

- Portfolio

- Approach

- News

Events

Posted August 18, 2025

- About

- Connect

Miller Hull embraces local context in embassy designs

Source: Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce

8-7-2019 | News

From Africa to Central America, the Seattle firm converts its sustainability “DNA” into major contracts with the Department of State.

By Sam Bennett

Special to the JournalIn his formative years as an architect in the 1970s, Dave Miller heard that famed Seattle architect

Fred Bassetti was designing a U.S. embassy in Lisbon, Portugal.

The thought that a Seattle architect could land a prestigious overseas contract with the U.S. government was inspiring to Miller at the time, he said.

Years later, when the opportunity came for Miller and his firm The Miller Hull Partnership to pursue an embassy project of their own, they didn’t hesitate.

“We thought, ‘Why not us?’” Miller said.

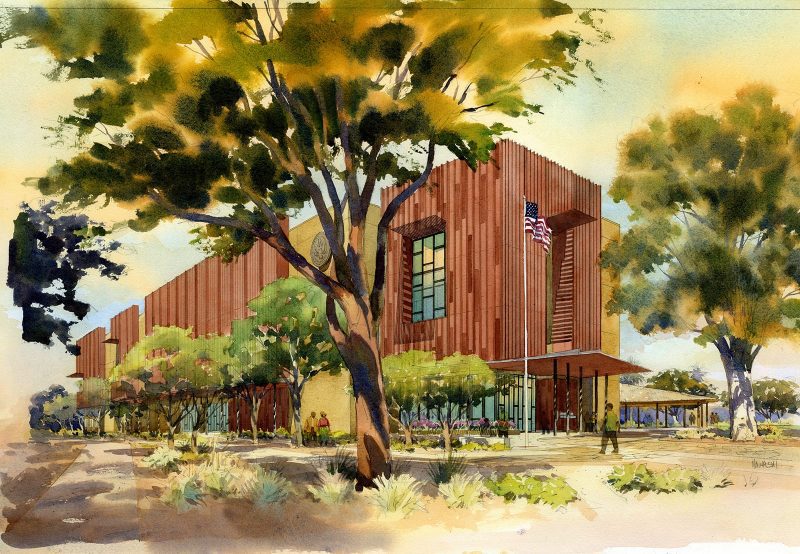

Miller Hull’s design for the U.S. Embassy in Guatemala City, on a sloping 9.4-acre site, includes an 18,000-square-foot, sustainably designed chancery building and Marine security guard residence. / Renderings courtesy of The Miller Hull Partnership

Propelled by the firm’s expertise in civic and cutting-edge sustainable designs, Miller Hull won a contract in 2014 to design five embassies and consulates around the world — from Latin America to Africa.

The highly demanding projects, overseen by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Overseas Building Operations, have sent the firm on an international trajectory that Miller only imagined in the 1970s.

“We’ve literally been up to our eyeballs in these projects for several years now,” said Miller. “It’s such an honor to represent the United States in these countries and design buildings that have to be respectful to the countries where they are being built.”

As design and construction on the first contract continues, the Miller Hull team will need to keep their passports handy for future travel.

Earlier this month, the firm won a second round of embassy and consulate projects with the Bureau of Overseas Building Operations.

The new agreement, known as an IDIQ, or indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity contract, commits Miller Hull to another five years of embassy and consulate work.

As part of the terms of the IDIQ process, Miller Hull made its submission for the design work without knowing where the facilities will be. “They’re very open-ended contracts,” Miller said.

What the firm does know is that the designs will need to adhere to strict requirements from the Bureau of Overseas Building Operations for each embassy and consulate.

When Miller began work on the first contract, he said he learned that the embassies and consulates are “being built in some of the toughest and most dangerous places, so the buildings have to be safe.”

Two of the Miller Hull-designed embassies are under construction — in Niger’s capital city of Niamey, and in Guatemala City.

The Guadalajara consulate compound is on an 8.5-acre site and includes a 36,000-square-foot office building and large, mature grove of trees.

Construction is set to begin soon on the firm’s consulate design in Guadalajara, Mexico. Design documents are complete on consulates in Casablanca and Merida, Mexico.

Miller Hull Partnership is one of several Northwest firms – including ZGF, Yost Grube Hall Architecture, Allied Works Architecture and structural/civil engineering firm Magnusson Klemencic Associates – who have been hired to design embassies and consulates in recent years. The costs of each project ranges from $60 million to $250 million.

As required by the Bureau of Overseas Building Operations, all embassies and consulates use the design-build process, working with a short list of government-approved building contractors, Miller said.

The design process begins with a site evaluation and assessment, then Miller Hull goes into concept phase and creates three designs. The Bureau of Overseas Building Operations reviews those designs and selects a preferred concept. When the firm reaches 50% of design development, a set of “bridging documents” is relayed to the contractor for reviews and additional details are refined.

“The relationships between the spaces and how they function are very prescribed” by the Bureau of Overseas Building Operations, Miller said.

In addition to visiting the sites before design begins, Miller Hull designers visit during construction. The firm partners with a local architect of its choice to help the design process.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

Many of the embassies and compounds are located in cities that have an indigenous, or pre-colonial, architecture as well as a colonial design vernacular.

“The colonial designs are what you see in the cities — such as the arcades and courtyards,” Miller said. “Those are elements that are pervasive in certain Mexican and South American countries. The colors and (building) materials are a big part of that gathering of context, which we take very seriously.”

In Niamey, Niger, which was first colonized by the Dutch in the early 1600s, Miller Hull studied the regional design context for its 10-acre embassy compound. The firm took cues from the local designs and incorporated materials for the 11,500-square-foot chancery building such as sand and concrete, as well as red metal oxide primer for the building exterior.

“Our buildings are expected to be a clear representation of the United States and our values,” said Sian Roberts, a partner with Miller Hull. “At the same time, we are guests in a host country and our designs should also be responsive and reflective of local traditions and climate. Studying the history and traditions of a place as well as the unique climate and ecosystem is one of the most interesting and rewarding parts of this work.”

Miller Hull’s extensive experience in sustainable design has been a valuable asset in the embassy compound work, Miller said. “Sustainability,” he said, “is in our DNA at Miller Hull.”

On a project-by-project basis, the firm has integrated photovoltaic panels for solar harvesting, when cost effective, as part of a federal performance goal adopted by the Bureau of Overseas Building Operations. The Guatemala City embassy compound, for example, is targeted to exceed federal energy performance goals by reducing consumption by 32% and providing 13% of the building’s energy with solar panels.

The embassy also is designed to treat and reuse wastewater onsite to reduce offsite flows. Wastewater is reused to provide 100% of irrigation needs.

“We are required to do a great deal of climate and energy analysis, as well as a thorough analysis of local utilities and systems for every site,” Roberts said.

The sustainability program extends well beyond the structures. Marilee Hanks, managing principal with the Portland landscape architecture firm Knot, said research into regional climates and vegetation informs her design decisions.

Miller Hull’s interior design for the Guadalajara consulate accommodates large numbers of visitors while also delivering a calming, welcoming experience.

Geometric patterns in southern Niger — caused by water and nutrient scarcity — are inspirations in her landscape solutions for the embassy.

“Evaluating ecological patterns found in the local landscape allowed us to drive design toward sustainability through an informed approach to planting, while also giving our team a beautiful aesthetic which happened to be driven by adaptation,” said Hanks, referring to her firm’s landscape design for the Niamey, Niger embassy.

Hanks said the Niamey embassy, like all the embassies and consulates she has done landscape design for, required “extreme sensitivity to cultural and environmental context.”

“We are always looking for ways to fit within a neighborhood and signal respect of place and customs,” Hanks said.

There is, however, a reason for sustainable design that goes beyond energy conservation.

“The more an embassy or consulate can be self-sufficient from a utilities perspective, the safer it is for the staff and better neighbors we can be to our host countries,” Roberts said. “Developing countries have limited urban infrastructure, and limiting our impact on local services is one of the best ways an embassy can demonstrate being a good neighbor.”

As part of Miller Hull’s contract, the firm did an extensive study on daylighting and energy performance.

SENSE OF WELCOME

Of equal importance, Roberts and Miller said the embassies and consulates must be “welcoming” places for sometimes large crowds. The Guadalajara consulate, for example, is designed to accommodate up to 2,000 visitors a day.

“For some, particularly in developing countries, the embassy might be the only real physical experience that visitors have with the U.S.,” Roberts said. “We take that role very seriously and are committed to creating a welcoming presence. Those seeking visas can come from very long distances and arrive early, meaning they may wait for hours in the elements. We provide shade and protection from the elements for consular visitors.”

The landscape architecture is critical to a visitor’s introduction to the embassies and consulates.

“The sequence of designed experiences through landscape for visitors should create a sense of welcome and convey a level of respect for the host nation,” said Hanks. “The design is largely shaped by careful consideration of desired visitor and staff circulation.”

For the 10-acre U.S. Embassy site in Niger, the Portland landscape architecture firm Knot incorporated a shaded courtyard and drew inspiration from native vegetation and regional ecological patterns.

With the new IDIQ contract, Miller said he is committing many of his designers and staff members to make the tight deadlines set by the Bureau of Overseas Building Operations.

The embassy/consulate work, he said, “is a huge part of our current workload and current mission, in terms of doing public architecture,” he said.

“It is difficult and stressful work,” Roberts added, “but I’ve found it to be among the most rewarding of my career. It is a great honor to be trusted with such important and significant design work. I have a much more nuanced understanding of the world and an entirely new perspective on world events.”

For Hanks, who has completed more than two dozen landscape designs of embassy and consulate projects for various Northwest firms, the projects have been a career-defining experience.

“The work has shaped my approach to design and firm management, especially due to my understanding of how similar and connected our global communities are,” she said.

As the design lead on several of the projects to date, Miller said he has found a “perfect role” as an architect.

Both Miller and his late partner Bob Hull served in the Peace Corps early in their careers. Doing embassy/compound work is the culmination of his early world travels with his passion for sustainable design that represents the best the United States has to offer, he said.

“We have an amazing group working on these embassies and consulates, and we love the work,” he said.

Related Articles

AIA Design Awards 2020

Award of Excellence & Hawaiʻi Energy Award Institutional Honouliuli Middle School Firms: Ferraro Choi And Associates, Ltd…

11-24-2020 | News

Perspectives. ‘Architecture of the Pacific Northwest’ Playing Cards

The Pacific Northwest is home to some of the most iconic architecture in the United States.…

2-25-2016 | Perspectives

Energy’s Forgotten Silver Bullet

Architects and engineers choose efficiency tactics to suit America’s widely varying climate, hydrology, and geography. This…

2-16-2026 | News

University of Arizona campus revamped for student success

A huge section of the University of Arizona has been revitalized and given new life by Miller Hull…

10-31-2022 | News

Miller Hull designs low-impact trestle cabin on Decatur Island

In 1987, Seattle architecture firm The Miller Hull Partnership started designing cabins on Decatur Island in…

6-23-2025 | News

09/2024 America’s Leading Interior Architects Forum: Jennifer Stormont

9-27-2024 | Events

××