Miller Hull

- Portfolio

- Approach

- News

Events

Posted May 15, 2025

- About

- Connect

Perspectives. COVID-19 Lessons for a Resilient Built Environment: A Roadmap

10-7-2020 | Perspectives

“The time to reassess our built world is now, not after the next catastrophe.”

.

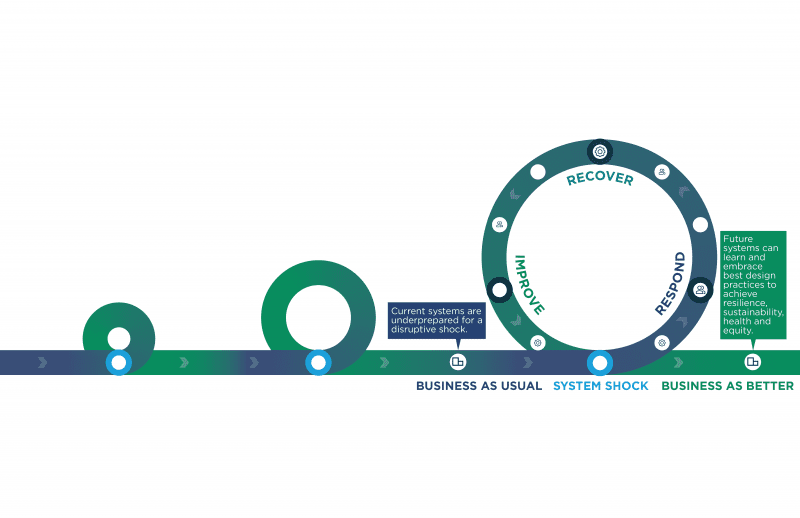

The rapid spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus resulting in coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has disrupted social, economic and cultural systems that sustain our patterns of life around the globe. This crisis has illuminated vulnerabilities in “business as usual” that give way under strain, disproportionately affecting the most disadvantaged members of our community and shutting down entire economic sectors that rely on physical proximity between people.

We are determined to learn from this system shock to build resilience in the environments that we design and face future disruptions more effectively. For the last six months, Miller Hull has been hard at work discussing, researching and working to strengthen our response to the effects of COVID-19 in the design and building industry. Our firm leadership and COVID-19 Response Task Force has collected, reviewed and disseminated recent research on best practices in lowing risk of transmission in built environments. Once we respond to the immediate health crisis, we believe we can recover to a new normal and improve our future buildings, using the pandemic as a catalyst to accelerate the transition to regenerative design. We believe that prioritizing the health of our buildings’ occupants is in line with our ongoing to sustainable, equitable and resilient built environments, further reinforced by our approach: BE BOLD. GO DEEP. DO GOOD.

PURPOSE

On September 10th, 2020 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported over six million total cases of COVID-19 across the United States. As we, Miller Hull, adjust our practice to mitigate the effects of the pandemic, we aim to leverage our experience as architects and researchers to help our collaborators, clients, and neighbors recover. Simultaneously, we strive to imagine a future where the shock of the pandemic acts as a catalyst, accelerating the design of future built environments that are resilient, just, sustainable and healthy.

This roadmap does not constitute new research; it is a synthesis of existing work, viewed through the post-COVID-19 lens, which we will share in more detail on our blog in the months to come. Its purpose is threefold:

1. To act as a common knowledge base, reviewing and cataloging possible actions architects, builders and building owners could play in the reduction of COVID-19 transmission risk in all projects at various stages of conception, design and operation,

2. To provide a framework that can be populated with new information as our own understanding of our role in response to the pandemic develops further, and

3. To imagine and illustrate how post-COVID-19 design could look, feel, and function learning from our own project successes and shortcomings, seen in the new light of the pandemic.

OUR PAST

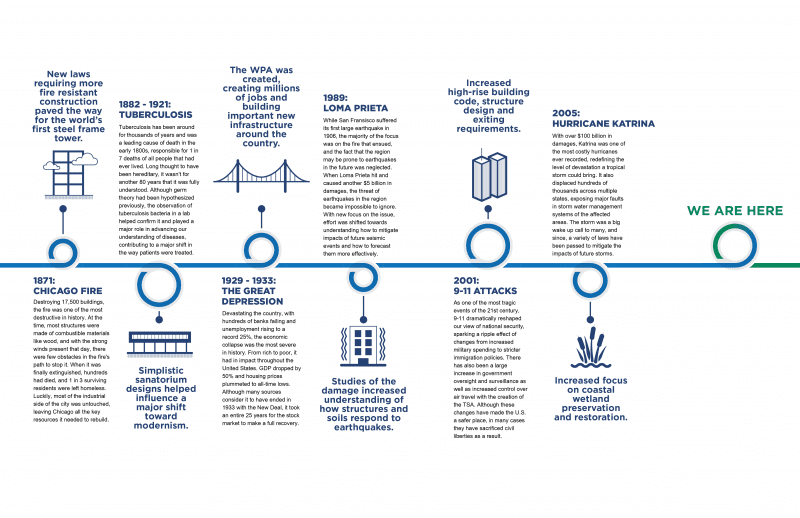

COVID-19 is not the first global disruption, and not the first disease, to catalyze change within architectural design. As far back as the 1st century BC, the language of architecture has been tied to that of the human body in Vitruvius’ Ten Books on Architecture; as recently as the last century, the modernist movement was shaped by a desire to harness the therapeutic powers of light and air in the battle against tuberculosis.

It is not surprising that the rise of modernism coincided with the rise of disease – both proliferated in dense, urban environments. Prior to the acceptance of germ theory, the presumed cause of urban disease outbreaks like tuberculosis and cholera was “bad air” caused by decaying matter – therefore, industrial era cities attempted to combat its spread through paving streets, separating dedicated sewage lines from public waterways, and creating public parks. Beyond outdoor spaces, modernist sanatoriums, hospitals and homes in the early 20th century were perceived as “curing machines,” deliberately used as one of the primary tools for disease prevention and treatment. Spaces to breathe fresh air, exercise, and sunbathe became staples of modern homes from Paris to Los Angeles. Meanwhile, the design of medical institutions began hybridizing and integrating with new medical equipment. Although the rapid development of medicine has gradually reduced our dependence on actively therapeutic built environments, the heritage of the modernist style is still felt today in buildings that demonstrate smooth, cleanable surfaces, ample access to daylight, and operable windows. Other shocks, such as the Great Chicago Fire, have also left their mark on built environments, catalyzing the adoption of now-commonplace technologies, such as the steel frame and elevators.

With this outlook on the history of built environments in response to crises, health-related and otherwise, we wonder what change will precipitate out of the ongoing pandemic. As architects living through this systemic shock, it is our task to reflect upon today’s crisis and use it as an opportunity to create a more resilient built environment going forward. Although it’s impossible to tell the future, we are certain that right now, we have a critical chance to learn and improve architecture for years to come.

OUR FUTURE

As architects, our duty is to protect the health, safety, and welfare of our buildings’ occupants, which places minimizing COVID-19 risk and building post-COVID-19 resilience squarely in our professional wheelhouse. This disruption is a call to action: one that invites, demands, and energizes all of us to think creatively and thoughtfully about the buildings we create for others. What are we doing on a daily basis to ensure more resilient structures that can gracefully withstand future disruptions? Can our buildings have multiple “modes” of existence that enable them to transition between various settings depending on the type of systemic shock? Could this type of architectural response push our concept of what constitutes a living building? Could we begin to envision an architecture that lives, weathers, and adapts to shocks along with its occupants?

COVID-19 is not the first systemic shock to have a profound impact on built environments, and it will not be last. As the world responds to the pandemic, we cannot lose sight of the ongoing climate crisis which is already affecting our planet’s capacity to sustain human life. Although different in temporal scales, the COVID-19 and climate crises share key characteristics – such as high momentum trends, irreversible changes, and disproportionate distribution of burdens – that can serve as valuable lessons for growing low-term resilience in our built environments. As architects, we recognize the continued imperative for urgent and sustained climate action that will mitigate and reverse damage to planetary health, as we seek ways to support human health during the pandemic.

APPROACH

Chain of Exposure

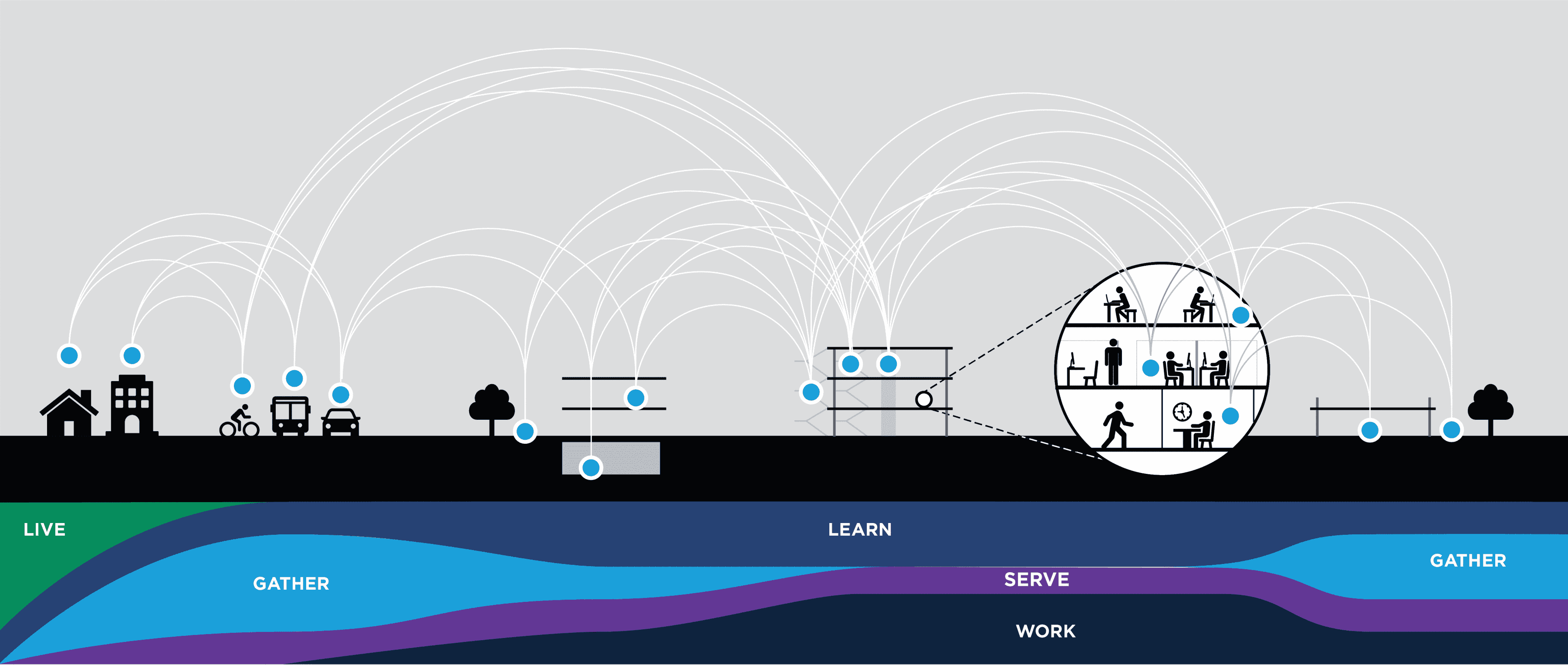

The occupants of our buildings traverse multiple built environments every day, from their home to the campus, office, or cafeteria. While we cannot prescribe or predict these paths, buildings that belong to the five Miller Hull market sectors – LIVE, WORK, LEARN, GATHER and SERVE – can influence choices that minimize risk of transmission along this chain of exposure. To catalog the range of possible design interventions to build resilience in a wide range of built environments, forthcoming blog posts in this series will be organized in sections corresponding to market sectors..

.

.

.

Transmission Risk

Following recommendations from the Center for Disease Control, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and The American Institute of Architects among others, the strategies catalogued in this blog series aim to minimize risk by targeting three possible transmission pathways – proximity, aerosol dispersal, and materials (fomites). While a zero-risk environment is impossible to achieve, we believe architects, building managers, and tenants can minimize risk of coronavirus transmission in buildings by applying a hierarchy of controls ranging from social distancing measures to engineering solutions. Since the body of work on COVID-19 continues to develop rapidly, many of these strategies are informed by past responses to similar acute respiratory viruses such as SARS and MERS.

Sustainability

The responses architects apply to reducing risk of viral transmission can have wide-ranging and significant implications on our sustainability goals. Re-examining Miller Hull’s work in advancing regenerative design, we find that many strategies that were initially implemented to promote long-term health for people and planet are now well-suited to deal with COVD-19-related concerns. Guiding principles like maximizing natural ventilation, improving indoor air quality, establishing a connection to the outdoors, and reduction of chemicals of concern, are excellent combatants of viral transmission.Perhaps one of the most important sustainable considerations to a built environment response to COVID-19 is how we temper them. Buildings and cities are slow to change and the infrastructure we put in place now will last. We have a responsibility to design wisely with a broad outlook, but we must not let our solutions come at the expense of the environment. From the possibility of increased energy use to the reflex of relying on the increased waste generated by one-time use materials, our responses to COVID-19 must consider impacts to environmental and human health.

Related Articles

Miller Hull embraces local context in embassy designs

From Africa to Central America, the Seattle firm converts its sustainability “DNA” into major contracts with…

8-7-2019 | News

11/2024: DBIA National – University of Washington Health Sciences Education Building: Elizabeth Moggio

The Tangible ROI of Teaming: Lessons Learned from the DBIA 2023 Best in Teaming Project Successful…

10-29-2024 | Events

New US Consulate in Casablanca, ‘lasting manifestation of lasting friendship’ American-Moroccan, according to Washington

The laying of the foundation stone for the new US Consulate General in Casablanca is the…

12-4-2020 | News

Five years later: Earth Day marks the fifth anniversary of Bullitt Center and showcases the success of sustainable design

By Chris Hellstern, AIA, LFA, LEED AP BD+C, CDT Living Building Challenge Services Director On this…

4-23-2018 |

AIA COTE Report | Lessons from frequent winners of the AIA COTE Top Ten Award

Miller Hull is included in this recent report from AIA Committee on the Environment (COTE) highlighting…

3-29-2017 | News

Archello Awards 2023 Longlist: New U.S. Embassy Guatemala City

Archello Awards 2023 has revealed its longlist for Government Building of the Year. The longlists celebrate the very…

10-11-2023 | News

××