Miller Hull

- Portfolio

- Approach

- News

Events

Posted May 15, 2025

- About

- Connect

An architect’s work is embedded in a community.

Research by: Jim Hanford, Michael Helmer, Katherine Martin, Brie McCarthy, Rio Namiki, & Jay Hindmarsh

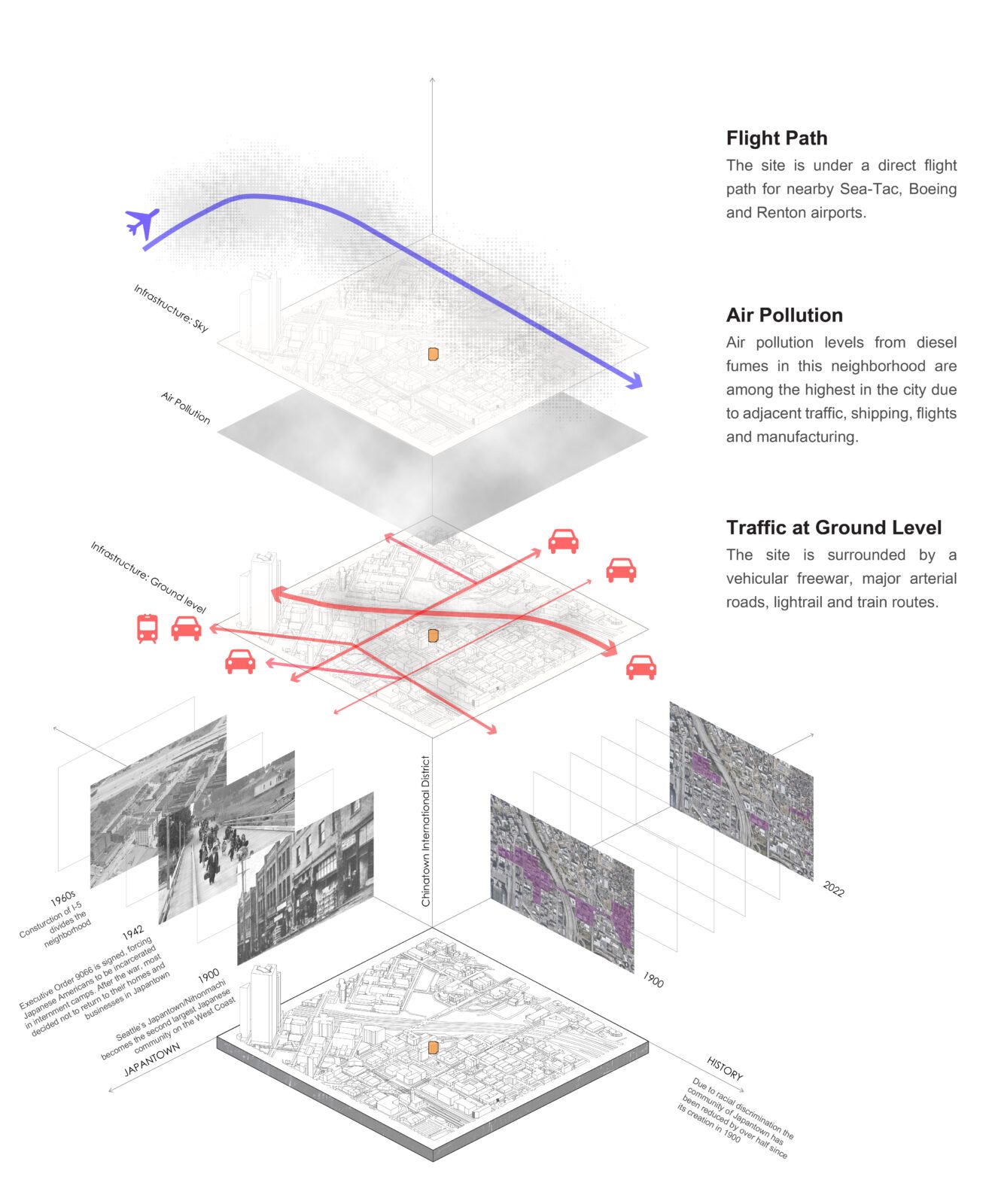

An architect’s work is embedded in a community. Although our nominal goal is to improve the lives of those coming into direct contact with our specific site, we have a duty to widen our lens and consider the spaces beyond. Often times, the urban space in which our site sits suffers from the continued effects of a racist history. From the way the highways intersect with and dislocate neighborhoods, to the location of the airport and industrial processes, so many places are negatively impacted by the developmental decisions guided by structural racism. Whether architects choose to accept this responsibility or not, we inherit these challenges, and have the opportunity to evaluate how our designs can begin to remake these neighborhoods in a way that honors those who live there.

The 2022 Energy Design Competition sponsored by the Seattle 2030 District called for a net zero energy strategy for the existing International Terrace affordable housing building located in Seattle’s Japantown/Nihonmachi. Miller Hull, along with its partners at PAE, Degenkolb, GLY Construction, and students from the South Seattle College Sustainable Building Science Technology program envisioned an opportunity to help heal this historically overburdened community while developing a renovation plan to enhance sustainability performance of the existing structure, and to ultimately avoid any future displacement of residents.

International Terrace is a low-income public housing building located at the intersection of 6th Avenue and South Main Street in Seattle, WA. The building, owned and operated by the Seattle Housing Authority (SHA), was constructed in 1973 and includes 100 one-bedroom residential units for a population of primarily aging-in-place Asian-Americans. There have been several upgrades and alterations made overtime, however a significant renovation will be necessary to achieve the climate and greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction goals outlined by SHA in their Sustainability Agenda.

The Seattle 2030 District has partnered with SHA to sponsor the 2022 Energy Design Competition which asks design teams to identify pathways to achieve net-zero energy and net-zero carbon emissions while finding ways to engage and assist the residents. Miller Hull is committed to reducing carbon emissions, and understands the important role that existing buildings play in achieving our climate goals. New buildings that are net zero are not enough – we must rethink our existing built environment.

In a collaborative effort, Miller Hull teamed with engineers, contractors, and students to formulate an approach that took to heart the residential experience, understanding that we couldn’t fully offer support to those who lived in International Terrace unless we recognized the history of the neighborhood, and the challenges that its people have faced.

History

Throughout the rich history of Seattle’s Nihonmachi/Japantown, the Japanese American community has been marginalized and displaced by racial discrimination. Before the settlers arrived in the 1850s, present-day Pioneer Square was home to a thriving Duwamish fishing village, where its residents continued to live and work as Chinese and Japanese arrived in the 1860s and settled to the east and south of Pioneer Square.

Since the settlement, Seattle’s East Asian laborers have faced racially discriminatory regulations like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Great Seattle Fire, the Jackson Regrade, I-5 Construction, and the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans and those of Japanese ancestry due to the Executive Order 9066. These events led to the displacement of thriving businesses and communities to their third and current location.

By 1900, Japantown was the second largest Japanese American community in the West Coast. This changed during World War II when Executive Order 9066 was signed in 1942, forcing Japanese Americans to abandon their homes and businesses to be wrongfully incarcerated in internment camps. Many chose not to return to Seattle after the war. The 1950s and ‘70s brought more disruption to International District, as I-5 and Kingdome construction physically divided the neighborhood, and fracturing the community.

Modern day Japantown has been significantly altered by this history, and has been reduced to less than half of the original size.

Health & Equity

In our proposal, the design team focused on low-carbon envelope, systems, and structural improvements that drastically reduce operational energy while following a “resident first” approach to decision-making that ensured occupant comfort and health were equally important as building performance.

Improved Air Quality

So, how does history impact modern day Japantown? Based on a site analysis generated by our team, in addition to utilizing the Washington State Environmental Health Disparities Map and Federal Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, we found air pollution to be one of the largest environmental exposure factors impacting residents health. With the i-5 corridor to the east and north, SoDo manufacturing to the south, shipping container ports to the west, and Sea-Tac flight paths overhead, air pollution levels from diesel fumes in this neighborhood are among the highest in the city. In addition, air pollution from wildfire smoke has increased throughout the city as a result of climate change.To begin compensating for some of the effects of long-term environmental discrimination, our team proposes that increased ventilation and filtration be added to International Terrace’s common areas through mechanical system upgrades, while through-wall heat pumps provide filtration and control outside air intake to individual units. Direct air intake and bathroom exhaust fans at the individual unit level can also reduce the spread of airborne diseases such as Covid-19. Improving access to clean air for an aging population can provide significant improvements in occupant health and wellbeing.

Energy + Carbon

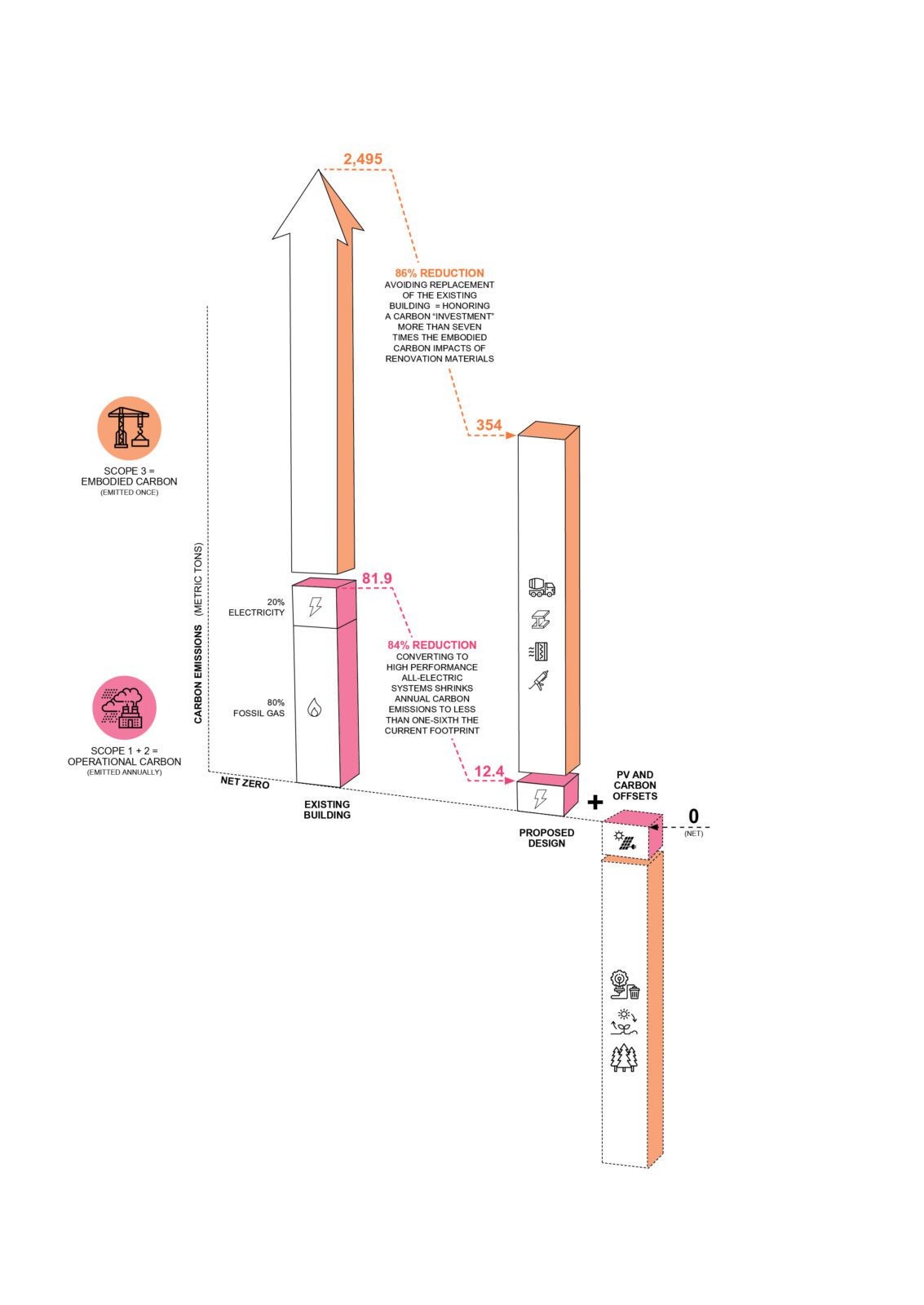

Ordinarily, when architects take on a project that includes a dated building in significant need of repair, rarely does the client want to keep the building unless it bears some type of historical significance. If the building is non-descript, and programmatically misaligned with its new intended use, it is almost always demolished, especially when rigorous sustainability goals are in place, the belief being that it is “easier” to tear down and start new.However, this approach does not take into consideration embodied carbon — also known as the quantity of emissions required to produce and install all of the products during construction — nor does it realistically predict energy usage over the course of the building’s lifetime.

Renovations typically require less embodied carbon since elements of the building can be reused, thus requiring fewer new products. Demolishing and building new, however, does not make use of any of the carbon already invested in the existing materials. In fact, a study by the Preservation Green Lab of the National Trust for Historic Preservation assessed that it could take up to 80 years for a new high-performing building to compensate for the environmental impacts of its construction, meaning even a net-zero building takes on a carbon debt when built new that it takes years to pay off.

Unfortunately, architects rarely have a say in whether existing buildings get saved. But as more of the industry acknowledges the value of existing buildings, we can provide Owners with new tools and knowledge to make better long-term decisions.

From an embodied carbon standpoint, our proposal for International Terrace wants to recognize the significant carbon investment that was made when this building was originally constructed. We can assume that the carbon emitted from the manufacturing of the original concrete and masonry structure was substantial, so it was important for us to keep as much of that material in place as possible and reduce or avoid any new materials that were not directly contributing to our high performance or resilience goals.

If we were to build this same building today, from the ground up, it would cost us around 2,500 metric tons of CO2e. We can extrapolate that roughly that amount of carbon was emitted back in the 1970s when this building was constructed – so this is the carbon investment that needs to be preserved. The renovation materials would cost us around 354 metric tons of CO2e which is only 14% of the original investment and affords us a retrofitted high-performance building with an increased lifespan.

Low carbon envelope materials used in the renovation include continuous exterior wood fiber insulation, synthetic stucco, fiberglass windows in lieu of vinyl, and low cement concrete for the shear wall retrofit. A thin brick cladding system was also selected to be applied at the exterior fin walls (in lieu of stucco) because it requires less maintenance over time, and brick has historical significance to the surrounding neighborhood. The team also investigated using thin brick and recycled brick to bring additional embodied carbon reductions to the project.

Disruption & Displacement

Seattle’s international District population has a history of displacement. Minimizing impact to resident routines and housing status was therefore very important to the entire design team.Many of the proposed structural systems and envelope upgrades may be conducted from exterior scaffolding allowing residents to remain in their homes during construction. Additionally, by implementing a floor-by-floor work plan, the numbers of residents required to temporarily vacate their units can be localized to that specific floor allowing all other floors to remain occupied. The residents of the floor under construction may be provided with a hotel room and storage space and can return to their homes when construction moves to the next floor. The idea of stacking to minimize the project’s impact on residents was based on input from previous SHA projects, and conversations with Walsh Construction, and further developed by our own contractor, GLY.

Improving the seismic performance of a building was also essential, as it can reduce the risk of collapse or life safety hazards to the residents, and decrease the risk of being displaced from their homes when a natural disaster such as an earthquake occurs. This eases the process of recovery for residents and increases the community’s resilience by reducing the likelihood of displacing a vulnerable population that may struggle to find alternative housing.

Aging in Place

Current residents reflect Seattle Chinatown International District’s predominantly aging East or Southeast Asian demographic and many live at or below the poverty level. In order for residents to reap the benefits of these proposed building upgrades, their environment must adapt to their changing needs as an aging population.To allow for aging-in-place, the design team recommends upgrading the units over time to be either Type A or Type B accessible units. Type A refers to units that are fully on Day 1 while Type B refers to units can be converted to accessible spaces when needed. Proposed accessibility upgrades include creating a larger bathroom and open kitchen to provide necessary clearances and mobility. A connection to an adjacent unit may also be opened to accommodate larger family sizes or remain closed to maximize available units.

Neighborhood

Community Resource Sharing

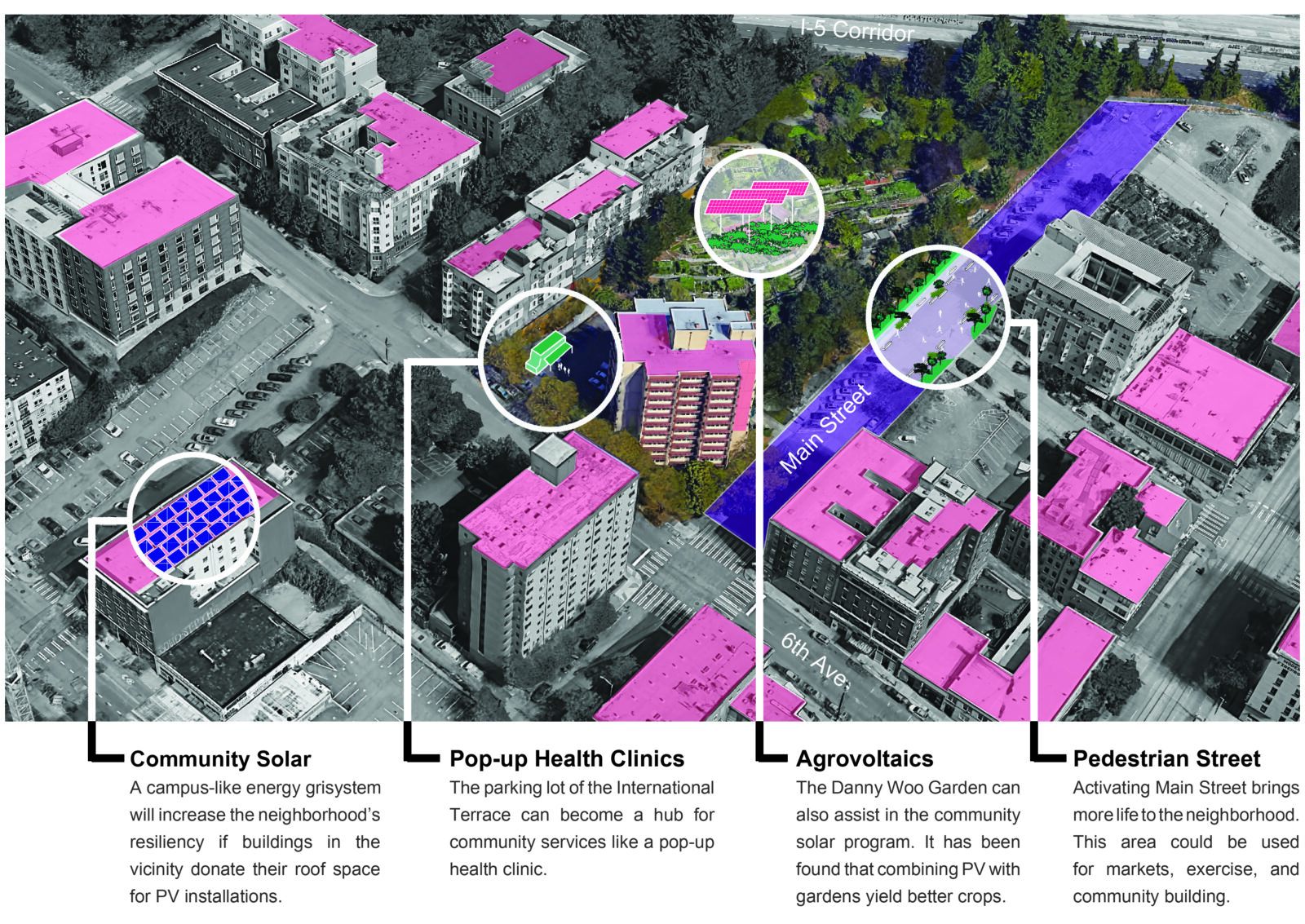

Formulating a net zero building from a blank slate presents fewer challenges than attempting to do so from an existing structure. This is why, often, when an existing building or site can’t satisfy its own needs, the deficiency of the current building combined with the presumed simplicity of starting from scratch leads many clients to demolish the existing structure. What is rarely examined, however, is the feasibility of utilizing community resources to offset the shortcomings of that individual building, which achieves not only practical gains for the offsetting of carbon, but also contributes to the avoidance of displacement.In this theoretical project, International Terrace’s location and height provided great solar access for on-site photovoltaic (PV) panels. However, due to the elevator overrun and mechanical equipment, only half of the roof area is available for a mounted PV array. The team decided to use the solid south wall area for vertically mounted PV panels, but also to offer an additional off-site but adjacent PV array or community solar investment to offset the remaining 80% of energy demand and qualify International Terrace as a net-zero building.

Our proposal suggests placing PV panels over garden and crop areas, which is known as an “Agrivoltaic Array.” The panels provide shade for plants and reduce irrigation evaporation which conserves water and boosts plant yields all while generating clean renewable energy. Creating an agrivoltaic array over the adjacent Danny Woo Garden could go a long way to closing the on-site renewable energy gap and support the needs of both the building and community, providing an exciting synergy between building energy demand and urban food production.

Similar to energy, rainwater can be collected from several nearby rooftops and captured in shared cisterns for reuse where needed. Currently, all rainwater that lands on the roof is drained directly into the city’s combined sewer system. A roof area of 6,800 SF and Seattle’s average annual rainfall results in approximately 145,000 gallons of rainwater captured per year that could be utilized on-site rather than draining to the sewer and contributing to overflow events into the Puget Sound.

Collecting and storing rainwater in on-site cisterns allows the project to reduce potable water demand by using rainwater for irrigation. While reusing water for toilet flushing within the building is possible, it would require substantial plumbing upgrades including filtration and a parallel piping system. However, the anticipated rainwater capture is more than enough to irrigate the proposed landscape improvements with excess water given to the adjacent Danny Woo Garden. In general, all adjacent land can benefit and flourish by utilizing rainwater collected by neighborhood buildings, while reducing irrigation demands from city utilities. As new buildings are constructed, they may also separate their excess graywater to be filtered and stored within the community.

Community-based resource sharing can reduce the region’s carbon footprint through a reduction in materials and waste, create jobs for locals, build community and social capital, and shift priorities away from material wealth thus improving mental health and wellbeing. Additionally, freeing up the City’s financial resources, directing them to more pressing matters like affordable housing, education, and community assistance programs, a Sharing Economy can create opportunities for improvement that would have otherwise not been feasible.

Pedestrian Street

International Terrace is located north of ID, at the original location of Maneki, the oldest Japanese restaurant in the US. Along with Nippon Kan Theatre and Panama Hotel, the original restaurant created an axis that was the heart of the Japantown. Currently, however, South Main Street east of International Terrace is an underutilized vehicular route due to the dead end at I-5.Our team believes that this street could be transformed into a predominantly pedestrian zone to increase walkability within the neighborhood and to support community events such as seasonal markets and fairs. To memorialize this community’s important history, our team also recommends that SHA conduct community outreach as part of any future renovations to address the history of the site. With a pedestrian street, the residents of Eco Terrace would be able to commute several blocks by foot without having to cross a busy vehicular street or intersection encouraging safe community interaction.

Reducing the height of existing site walls, introducing low plantings, and providing landscape seating allows the building entry to be more visible and welcoming. The corner lot location also allows Eco Terrace to become a prominent anchor to the new pedestrian street activities. These recommendations are based on finding ways to activate and re-establish the strong pedestrian connection that once existed in Japantown.

Conclusion

As the associations between health and planet-positive architecture become increasingly evident, more organizations are choosing to invest in high-performance and low-carbon construction. The majority of these companies, however, are large private entities. But the 2022 Energy Design Competition envisions bringing a level of investment usually reserved for high-budget private clients to the public realm, and, more specifically, to vulnerable populations, like those who live in Seattle’s Japantown that bear the brunt of the climate’s degradation.

Because International Terrace serves a community that has an unequal vulnerability to climate change, Miller Hull felt that immediate carbon reductions over the next 30 years would be more beneficial to this population as opposed to slow reductions over a larger timeframe.

The proposed upgrades to International Terrace provide a clear path toward an equitable and sustainable future for the residents, surrounding community, and the country, at large.

Outlining the feasibility of achieving net-zero on a low-budget, and forecasting the possible resulting neighborhood improvements, this proposal provides a template for how to use sustainable infrastructure to build community, and reinforce identity. Through a hyper-local approach and the consideration of not only the residents but their community and history, a building can become of its place in every meaningful way – its economy, ecology, and culture.

By driving down operational energy demand through building electrification and envelope improvements, the building is able to achieve a 45% energy reduction compared to existing operations. Combined with on-site renewable energy, Eco Terrace will qualify for the upcoming WA Clean Buildings Act threshold. The remaining operational demand can be met with an off- site PV array or community solar investment achieving net-zero energy status.

Furthermore, extending the existing building’s useful life with targeted upgrades and low carbon materials ensures that the original carbon investment is preserved, and total carbon emissions will be significantly fewer than constructing a new building to serve the same purpose while also qualifying for upcoming Seattle Building Performance targets.

In addition to achieving high-performance and low emissions goals, the proposed upgrades greatly improve occupant health by addressing air quality, accessibility, and equity concerns within the area. This ensures the current and future residents of International Terrace reap the benefits of these upgrades while also strengthening their community for generations to come.

Extending beyond the building’s footprint, opportunities for neighborhood resource sharing, community garden integration, and improved pedestrian access help to create a safe, healthy, and resilient community. Construction costs can be achieved through a combination of City, State and Federal funding sources allowing International Terrace to become a catalyst for further equitable and sustainable investment within Seattle’s International District and beyond.

××